For nearly three decades, Eminem has been a cultural touchstone. His music has provided a soundtrack to the lives of millions, and his lyrics have mirrored the anxieties, frustrations, and triumphs of generations. But beneath the bravado and shock value, there’s a complex man named Marshall Mathers.

Complex’s Chief Content Officer, Noah Callahan-Bever, wrote an extended obituary to Slim Shady, tracing his story through his own experience. You can read it in full on the magazine’s website >>> or here below.

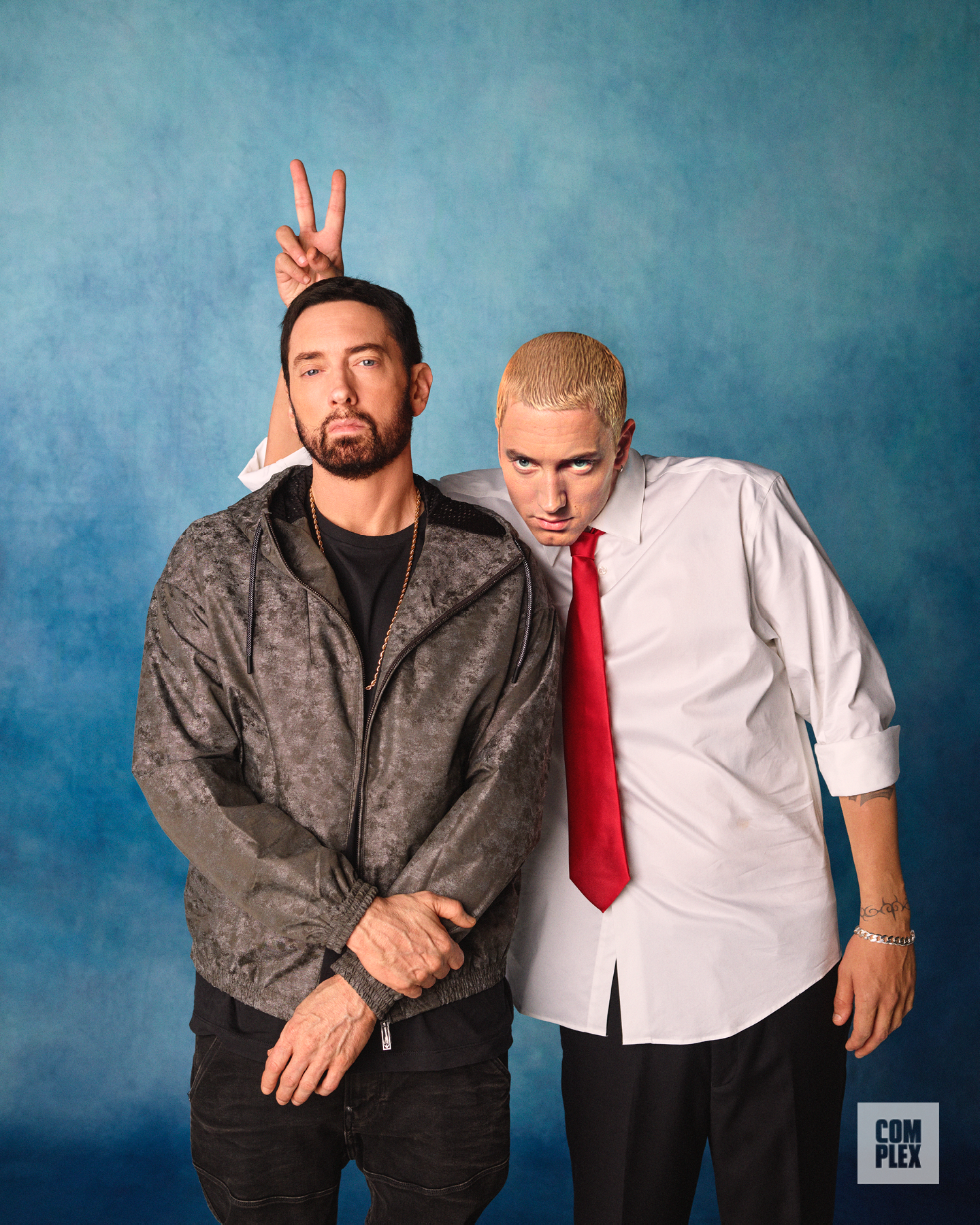

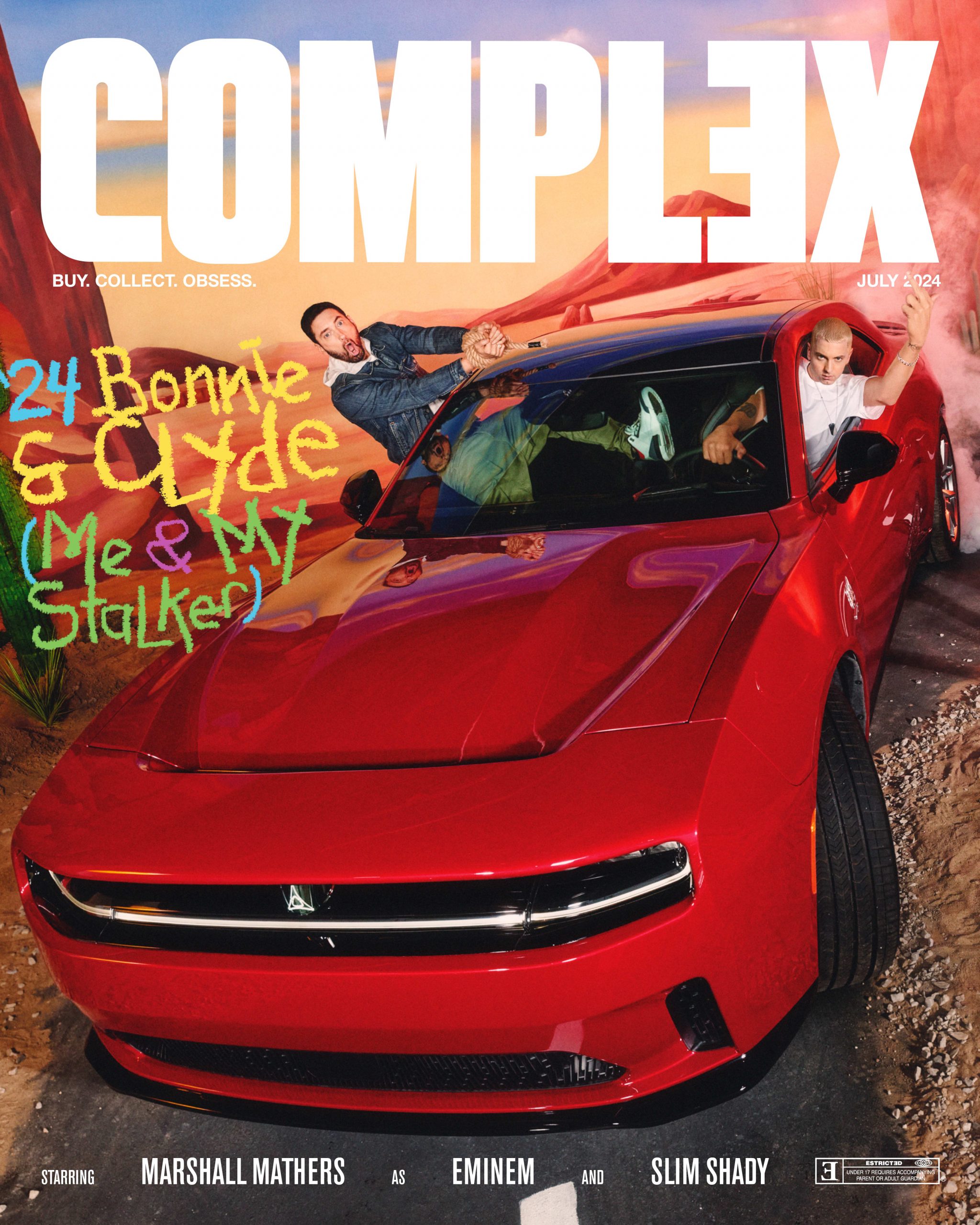

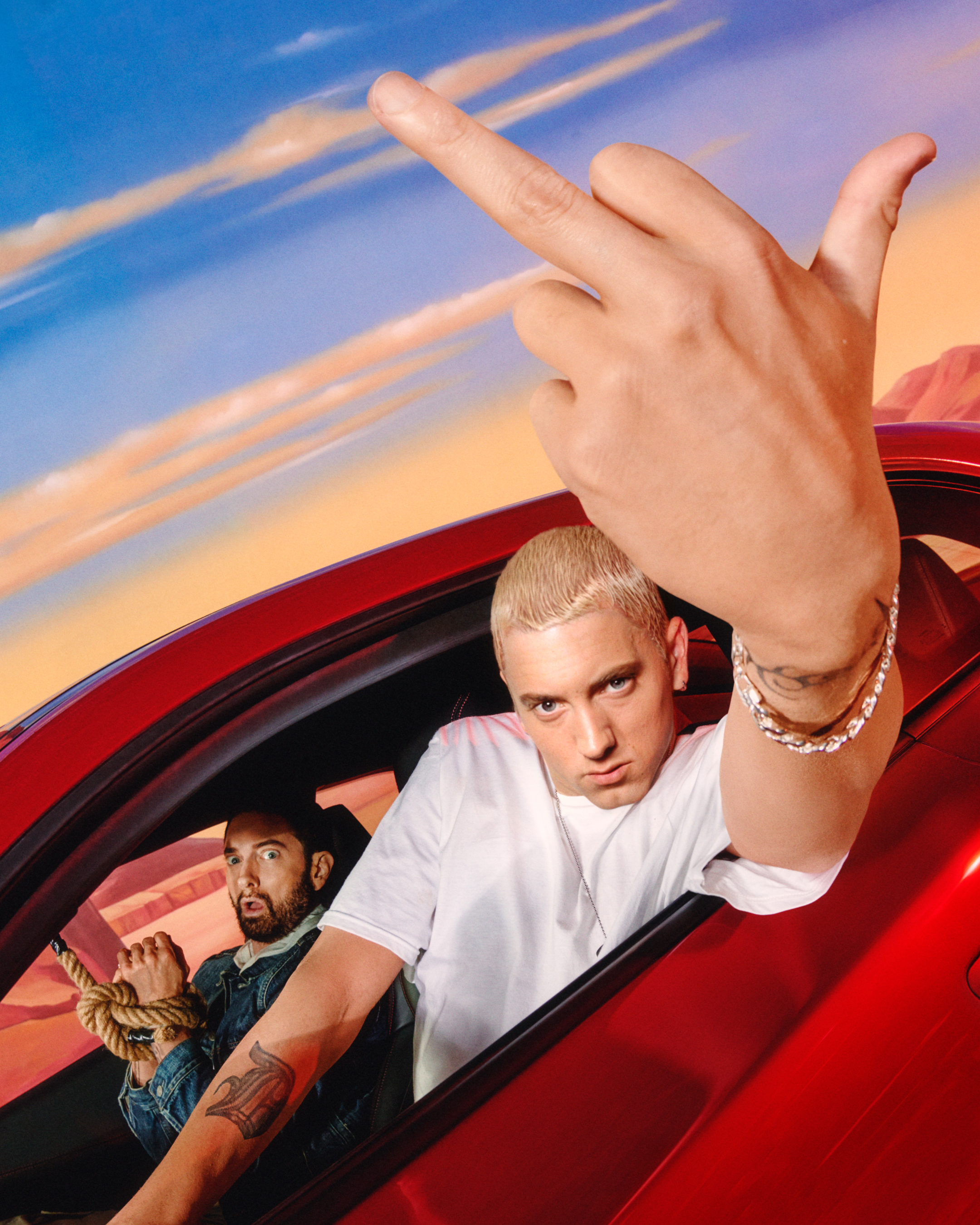

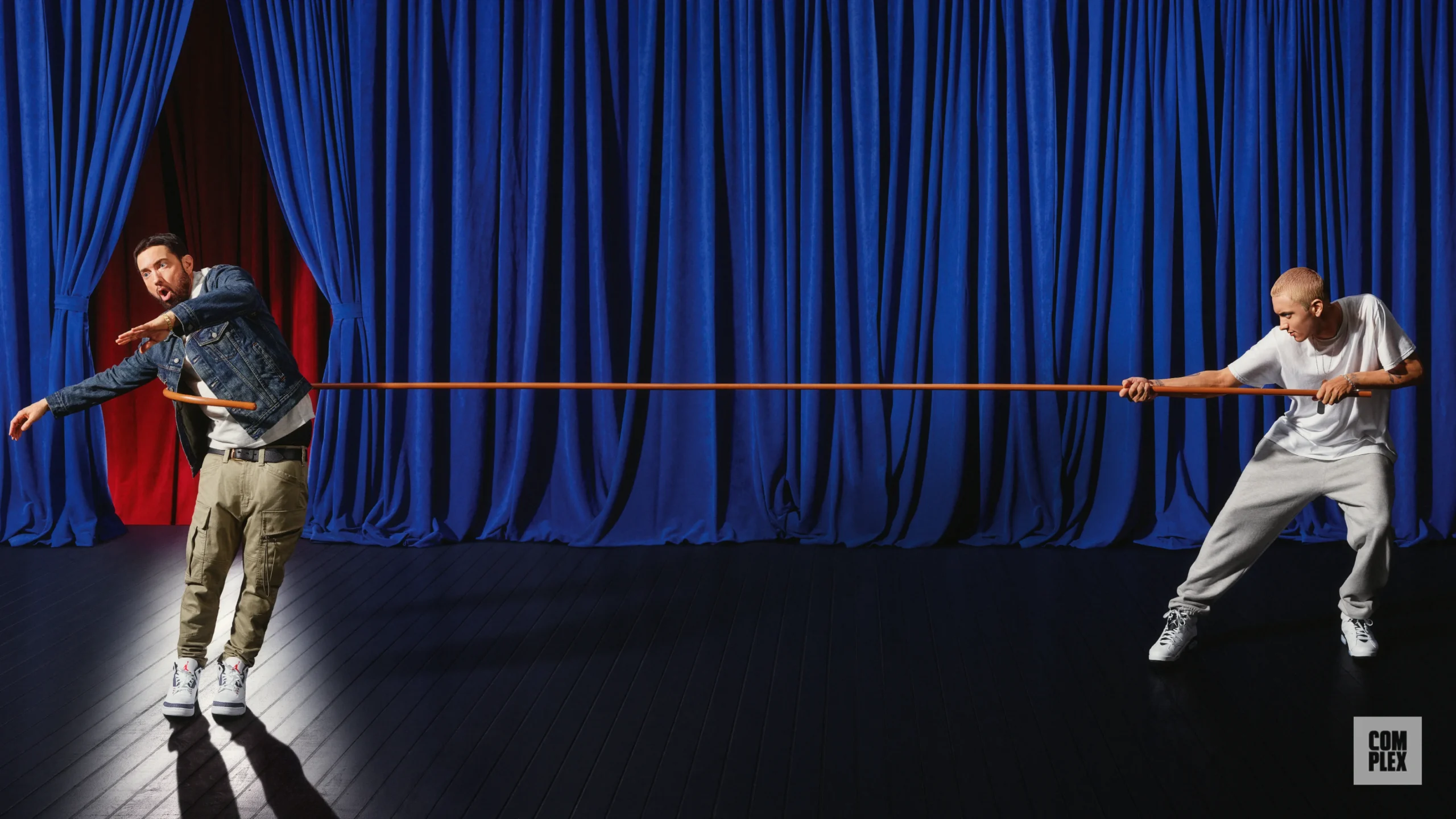

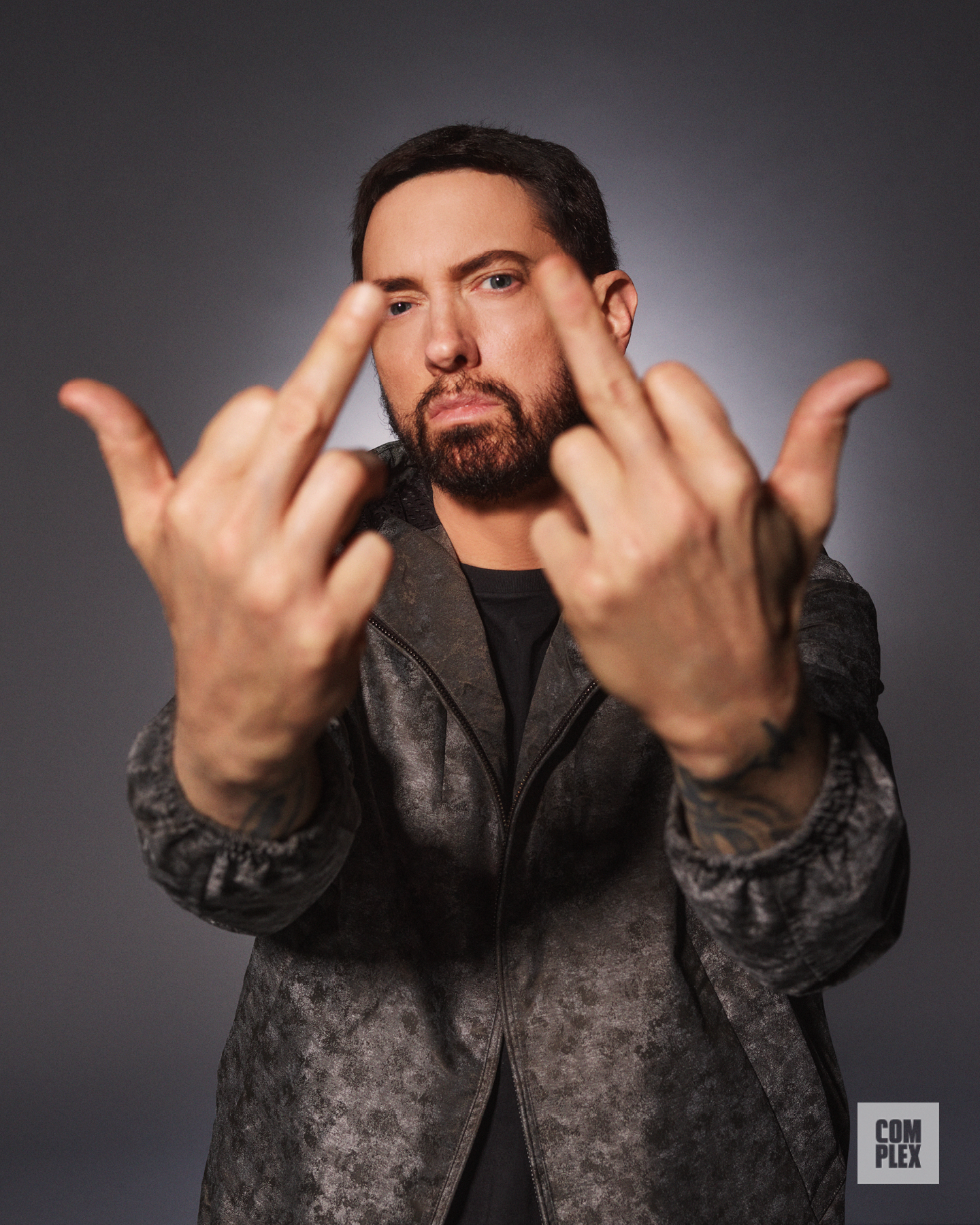

The story is accompanied by a technologically complex photo shoot representing Marshall and Slim Shady. The magazine uploaded a video showing how the work was done.

SLIM SHADY VS. MARSHALL MATHERS COMPLEX COVER STORY

Dearly beloved,

We are gathered here today to celebrate a life that was both loved and hated in equal parts, the world over. A godhead of the grotesque who clawed his way to the top, only to pop a squat on the planet and drop a culture-shifting deuce. A provocateur who roasted the corny with impunity and impugned hypocrites, left and right. An American rapscallion who rapped his ass off while showing America its ass. A fearless advocate of fart jokes, felching, and fear and loathing—not to mention a bit of the old ultra-violence. A juvenile offender whose Freudian fight-or-flight reflex murdered his superego and inflated his id into a monstrous abomination comparable only to The Man With the 10-Stone Testicles.

But unlike Wesley Warren Jr. (RIP, you really let your nuts hang, too, bro!), this is not a man of whom I speak. This is an idea. This is the spirit of Detroit. This is the conjuring of a desperate artist—down to his last dollar and teetering off the edge of sanity—while clenching on the crapper. This is salvation through savagely free speech. This is… Slim motherfucking Shady.

But now we must mourn—because Slim is no longer with us. That’s right, the evil imp has been offed by the very man who sired him. So we take this time to remember him.

Everyone has a story about the first time they met Slim. This is mine.

It was June of 1998 and I was an editorial assistant at an upstart hip-hop magazine, BLAZE. A 19-year-old NYU freshman at the time, I had just scored my first business trip—an assignment in Los Angeles(!) for the premiere issue of the magazine. Since I had roughly $50 to my name, a friend who was also in LA for the week, DJ Max Glazer, picked me up at LAX in his rental car. All I had was an address of a studio scribbled in my notebook and the assurance of one Paul D. Rosenberg, Esq., that I could find the subject of my story—a then-mostly-unknown Detroit rapper named Eminem—thereabouts.

See, about two weeks prior I was hanging out at Fat Beats in downtown Manhattan on a Saturday morning, as I was wont to do back in those days, and a tall gentleman in a suit popped in and started making conversation with my guy Max, who, it so happens, was in the DJ booth spinning. A few minutes later I’d see a CD passed between the two and then, suddenly, the store started to shake to an epic kickrub, followed by the simultaneous symphony of Labi Siffri’s bassline from “I Got The…” and that unforgettably nasal declaration: “Hi, my name is!” The voice was instantly familiar—I’d scooped up the 12” for “Just Don’t Give A Fuck” at the top of the year, having previously heard Eminem scorch Shabaam Sahdeeq’s “5 Star Generals,” and was pretty taken by Em’s mix of wrought lyricism, piercing tone, and off-the-wall creativity—but now he sounded waaay more confident and precise. Also, the music was 20x bigger than anything I’d heard him spit on.

But now we must mourn—because Slim is no longer with us.

I walked over and asked if this song was, in fact, by Eminem. The tall man said yes, and that Em had recently signed with Dr. Dre’s Aftermath Records, and that this was a rough mix of the first song they’d recorded. I introduced myself and he told me his name was Paul and that he was Eminem’s attorney. We exchanged information and I brought the intel back to the BLAZE office, pitching a story for our new artist section. As you can imagine, being the lone teenage white kid working at the rap magazine, championing a white rapper was a position about which no one could be less enthusiastic than I was. And my interest was, unsurprisingly, met with a healthy volume of skepticism. But I got Jesse Washington, the EiC, to meet with Paul and as soon as he heard the record, Jesse sent me to LA.

So here I was with Max, pulling into a nondescript strip mall in Burbank, CA, feeling confused. It looked like every other strip mall in America—a nail salon, a Chinese restaurant, a UPS store. This did not look like a place where people would record music. Eventually we wandered around to the back alley and spied a black Town Car with the windows rolled down, blasting earth-shattering bass. Max and I cautiously approached.

Seated in the front were a Black dude and a white guy, bobbing their heads furiously. I tapped on the door of the passenger side and the white dude looked up. Draped in oversized black sweats, with that same damn Nike Air hat cocked to the right revealing short brown hair, he looked vexed that I’d blown his buzz. I quickly explained that I was “Noah from BLAZE.” He introduced himself as Marshall, and his friend in the driver’s seat as Royce. He said they were listening to a mix for his album, and told us to get in the backseat. Now mind you—having heard the macabrely cartoonish “Just the Two of Us”, a B-side on his aforementioned independent single on which he explains to his toddler, in baby talk, why they’re dumping mommy’s body in the lake—I felt like I had a stomach sturdy enough for Eminem’s dark humor.

The more dejected Eminem became, the looser he got with his language and the ideas anchoring his bars became more unhinged. Eventually, he personified this idea and then christened it: Slim Shady.

But you know what I wasn’t prepared for? Slim Shady. And that was what I got as soon as Marshall pressed play. Over fluttering guitar licks, a rolling bassline, and more kickrubs (he really loved those back then), what starts like a regular underground rap verse quickly spirals into some of the most depraved storytelling ever committed to 2” tape. First, an unprovoked high school fight with an overweight girl at the local pool ends in the young lady being tossed off the diving board. B-b-b-but wait, it gets worse. In the next verse, an attempted robbery of a (presumably the same, now adult?) fat woman goes sideways as the victim fights back. Slim, high on crack with a broken back, then sidesteps her attempted seduction with a violent outburst that culminates in the blood-curdling, hyper-realistic sounds of death by dick. Blech. “As The World Turns,” indeed.

Our jaws on the ground, Max and I stumbled out of the car stunned and a little sickened, giggling nervously. I whispered to Max that I felt the same discomforting titillation as the first time I listened to 2 Live Crew’s “Dirty Nursery Rhymes” or N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton. Everything about it was wrong. Abhorrent, even. Still, lyrically it had gripping, Slick Rick-level storytelling and dexterous wordplay. And that’s the thing: Slim may have been extra foul with a side of stupid, but he was also very acutely self-aware and entirely unserious. It was very clear that—more than any of the many, many anti-social sentiments expressed—provocation was the only point around which he had any conviction. And I, for one, was provoked.

Golf clap, Slim. Mission accomplished.

I would spend the next week shadowing Eminem as he added the final touches to The Slim Shady LP, and would discover across songs like “My Fault” and “Cum On Everybody” that what I’d heard in the car was not an outlier. Mostly, Em and I lounged around the studio and the furnished apartment that Interscope was renting him, making occasional trips to Taco Bell. He was on a strict regimen of Vicodin and Zima. It’s hard to overstate what a humble, kind, and thoughtful guy Em was. Anytime I lauded his prospects, he would literally knock on wood and say, “I just want to go gold. If I can do that then I can put aside enough money to get a house and save for my daughter’s college.” He would also say things about his career that are quite funny in hindsight, like, “I’m not trying to be no 30-year-old rapper, youknowwhatImsaying?” (To be fair, in 1998 Rakim was 30.)

Speaking of rap, we talked a lot about rap. I was surprised that Em’s opinions were very heterodox for a denizen of underground rap. He argued that 2Pac was the greatest rapper ever because “he said the most important things,” but that Biggie had made the best albums. He and Royce offered praise and peer-to-peer critical analysis of Pun and Big L, who were both peaking that summer.

This is going to be hard to believe now, but at that exact moment in ’98—since they were the two most lyrical underground prospects to get signed to majors—Marshall was in a Caitlin Clark/Angel Reese-type unspoken cold war with Canibus (hence Em’s friendly elbow-in-the-lane bar on “Role Model”). So there was a lot of speculation amongst me, him, and Royce about whether or not ‘Bus would deliver on his upcoming longplayer. Two months later we’d all learn that he didn’t (it was kinda a whole thing at BLAZE).

Eventually we pushed through the surface rap-dude convo and things got more personal. He showed me pictures of his then 3-year-old daughter, Hailie Jade, and explained the desperate poverty he prayed he was on the cusp of escaping. And that, he said, is exactly where Slim Shady came into the picture. He told me about his 4-track demos in the early ’90s; his rise on the battle rap circuit at Maurice Malone’s Hip Hop Shop in Detroit; the disappointment of dropping his first album, Infinite, to essentially no acknowledgement; a disputed (by him and Royce, at least) battle loss to Chicago freestyle legend Juice; and the bittersweet frustration of coming in second at the Rap Olympics. In aggregate, he’d endured nearly a decade of rejection and dismissal—compounded by the breadwinning pressures of fatherhood—prior to the still pending, and still anything but promised *overnight success* that would come via Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine.

And out of his frustration that his obsessive dedication to craft was simply not enough, he explained, came a revelation. The more dejected Eminem became, the looser he got with his language and the ideas anchoring his bars became more unhinged. Eventually, while dropping the kids off at the pool, he personified this idea and then christened it: Slim Shady. With no fucks left to give, he lost all filter and flooded the zone with morbid, biting humor, graphic scenes, and explicit langage.

And although this new attitude got the snowball rolling independently, the good Dr.—a man who’d minted millions off of N.W.A, Snoop Doggy Dogg, and 2Pac’s combo of high-quality music and high-controversy content—was deeply convicted that Em had only scratched the surface of how spine-tingling, hair-raising, and/or nauseating (depending on your disposition) Slim could be, and encouraged Em to lean into it, and quadruple-down. Which, as I’d just discovered, is exactly what he did.

I’d see Em several more times during that summer and fall as he’d pass through my hometown, NYC, on the Lyricist Lounge Tour and for various other promotional activities. I’d roll with him to Stretch & Bobbito’s WKCR show as well as the Bad Meets Evil sessions. We’d even get stuck in an elevator together. But through most of that, while the legend of Slim Shady was quietly gathering, outside of the booth he was still very much just Marshall.

It wasn’t until January of 1999 that I’d truly get to see Slim Shady consume his entire identity. Eminem was in town for his first headlining gig at Tramps (MF Doom and Sir Menelik were the opening acts) and the launch of the “My Name Is” video on TRL. Anyhow, Em hit me—he’d gotten a cell phone by then, and was still easier to reach than the president—and told me to swing by the Cutting Room, where he was recording with Tha Outsidaz.

I walked in and my eyebrows hit the ceiling, an involuntary reaction to his newly bleached blond hair. I’d seen it in the video, and on stage, but not IRL. He laughed and said, “This is my one shot and if I wanna stand out, I need everything to be memorable. I feel like the raps are memorable. Dre gave me really memorable beats. And I need the visuals to be memorable, too. Not just the video, but me, too.” And then he explained the mixed feedback he’d gotten from the suits and programmers on “Just Don’t Give A Fuck,” a black-and-white, very DIY-feeling clip.

An hour later, he asked me if there was a McDonald’s nearby and we walked up Broadway to the Mickey D’s on the corner of Waverly Place for lunch. We sat in the front eating and catching up, enjoying the same anonymity we’d always known—just a couple of guys in baggy, sagging jeans with backpacks and beanies bullshitting. Until I started to notice over Em’s shoulder a gaggle of teenagers—mostly Black girls I’d ballpark as junior-high age—starting to assemble, staring at us and whispering. I guess I knew, in the abstract, that Em was becoming famous, but up until that point his Fat Beats notoriety had a perimeter that ended on the corner at Gray’s Papaya. Clearly, though, things had changed, and I was not privy to the new shit.

The cacophony was deafening as the kids cornered our table, thrusting anything on their person at Em to autograph. Eyes wide, Em looked completely overwhelmed. The Slim Shady gambit had worked.

In less than a minute the group swelled from four to 12 and whispers turned to full-throated yelling.

“OHMIGOD, ITS SLIM SHADY!!!” “YO, SLIM SHADY’S EATING AT MCDONALDS!!!” “BRO RAP FOR US!!!”

The cacophony was deafening as the kids cornered our table, thrusting anything on their person at Em to autograph. Eyes wide, Em looked completely overwhelmed. The Slim Shady gambit had worked. All he’d ever wanted to be was a successful rapper. However, it’s truly impossible to understand the reality of what that looks and feels like until you’re knee-deep in it. We quickly stood up, he scrawled an “S.S.” signature on a couple of notebooks, a backpack strap, and even a cheeseburger wrapper, and we got the fuck outta dodge. Of course, neither Em or myself had any real idea, but this was just the tip of the iceberg.

We all know how the rest of the story goes. On the back of Slim’s magnetic persona and his ability to capture a fourth-wall-shattering meta-narrative of him watching the audience watching him watching the audience, Eminem would go on to sell more records than nearly anyone in the history of recorded music. The drugs he would use to numb himself from the whirlwind that had become his life—which included extraordinary stresses beyond fame and fortune like a couple of failed marriages and the murder of his best friend—would go from a recreational hobby to a professional crutch to a near fatal overdose. When he thankfully went sober, Em would try to resurrect Slim to a mixed response, before finally letting the caricature go and channeling his own personal growth into an emotionally revealing and technically rigorous, if somewhat grim, oeuvre of hit records and No. 1 albums that pointedly distanced himself from the cartoon-ish character that both broke him as an artist, and then him as a person.

Which brings us back to why we are all gathered here today. It’s 2024 and Eminem is entering his third act. What exactly it will bring, I do not know. But what I do know, is that having spent short bouts of time with Marshall every couple of years for the last two-and-a-half decades—and experienced him in his friendly, if frustrated, obscurity; his paranoid, self-medicated daze; and then the serious early days of his sobriety—he seems now, dare I say, relaxed… and, even, happy?

During the several days that we worked together on capturing the photos for this cover and the Face-Off digital short, I got to spend more face time with Marshall than I had since ’98. Yes, he still has—without any sense of clinical authority beyond having read Walter Issacson’s Steve Jobs bio—what I would describe as a neurotic obsession about absolutely every element of his process and his product. And he is absolutely as competitive about his craft as he was standing in front of that mic at the Wake Up Show in ’98. All of which can be heard on his latest, The Death Of Slim Shady (Coup De Grâce). The attention to detail is maniacal—everything from the the way he threads ideas and references between the album lyrics, the music videos, and even our Face-Off short, to rhyme schemes and multiple entendres, to the ad-libs and orchestration, to the purposefulness with which he darts in and out of each character’s voice. And then there’s the intentionality of the pacing and sequencing; how he doles out narrative revelation with pointed parsimony, such that even Christopher Nolan would tip his hat.

He has a dedication to his craft that is superhuman, and also, at this point, solely self-motivated. He’s achieved every professional accolade many times over, and earned enough money that his grandkids’ grandkids will be using gold bars for Lincoln Logs. Honestly, as far as I can tell, the only thing that animates his continued creation is the desire to outdo himself and continue to earn the respect of his peers. As a creative of a certain age, I can’t front, it’s downright inspiring to witness.

But he also had an ease about him. No eggshells were being walked upon. The vibe was creative and collaborative, and many times we even got to see Eminem smile—without Photoshop. I certainly wouldn’t pretend to know Marshall well enough to say he’s “at peace” or anything, but it was absolutely uplifting to see him so easygoing and emotionally free. This guy sacrificed everything for his art, and for his audience, and it’s genuinely satisfying—having known him through the meteoric ups and frightening downs—to see him come out on the other side of it all in a truly better place.

So maybe that’s why Marshall decided that Slim’s gotta go. He’s a matured master of his discipline who has transcended the need to court controversy, or to vent rage. He knows there’s no country for old men, and there’s even less room for an aging agent provocateur. The same anti-social musings that sparked outrage and exhilaration in ’98, are, today, met with equal parts performative pearl-clutching and shouts of “passé!” People complain the Overton window of acceptable discourse has narrowed, while Ye brazenly kicks down the wall like the Kool-Aid guy at InfoWars and says a litany of things that make Alex Jones look like a moderate. Simply scroll your “For You” tab on X for 30 seconds and you’ll likely pass a dozen posts more offensive than anything Slim Shady ever wrote. And he wrote “Fack.”

And so we bid you adieu, Slim. And we thank you for saying things we were thinking but too scared to say.

And so we bid you adieu, Slim. And we thank you for saying things we were thinking but too scared to say. And for saying things so depraved we didn’t even know they could be thought of, let alone said out loud. And for skewering our heroes, and calling out our hypocrisies.

But here in the shadow of Slim’s passing is no time to wallow. He went out with a bang. Literally. So sing for the moment! Speak truth to power! Let ‘em know how you really feel! Send that mean tweet! Hit the group chat with a joke that would get you and everyone in the chat tried at the Hague! Yodel like Yoda yelling “Yolo!” in Yorùbá with two Sith señoras, sitting shotgun in the back of a hatchback Toyota!

I guess—dead or alive, 19 or 45—there’s a Slim Shady in all of us.

Pause. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯